|

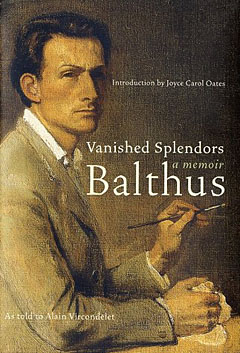

Balthus,

Vanished Splendors, cover Balthus,

Vanished Splendors, cover

Balthus,

Thérèse Dreaming, 1938, oil on canvas, Balthus,

Thérèse Dreaming, 1938, oil on canvas,

collection

of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY collection

of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY

|

|

A secretive painter who defied lables

By Dan Tranberg

Known to the world simply as "Balthus," Balthazar

Klossowski was among the most enigmatic painters of the 20th century.

Born in Paris in 1908, he spent the bulk of his life secluded from the

public, produced some 350 paintings and 1,600 drawings and died in February

2001, 10 days before his 93rd birthday.

Though his paintings, which often depict girls in various states of undress,

can be found in some of the world's greatest museums, he remains an ambiguous

figure whose work never really fit into any major school or movement.

Some critics tried briefly to align him with the surrealists, because

of the dreamlike quality of his images, but the artist vehemently rejected

this. Others thought his work verged on pornographic, which, again, he

strongly denied.

So, who was Balthus? What was his deal?

"Vanished Splendors," the posthumously published memoir he dictated

to French journalist Alain Vircondelet, provides some answers but is far

from a juicy tell-all. Through its breezy, stream-of-consciousness narrative,

he emerges as a man earnestly trying to secure a sense of dignity and

respect. By and large, it works.

Balthus came from an intellectually privileged environment. His father

was a Polish art historian, painter and critic whose close friends included

Andre Gide and Pierre Bonnard. Two years after his parents separated in

1917, his mother became the lover of poet Rainer Maria Rilke.

Under Rilke's tutelage, the young Balthus began to flourish as an artist.

In 1921, when he was only 12, Balthus published a book of 40 drawings

with a preface by Rilke.

But although his early ties to the European intelligentsia obviously helped

him, Balthus spends much of "Vanished Splendors" describing

his personal life as a spiritual search rather than a climb to celebrity.

"I cultivated the taste for a certain secrecy not in order to make

myself important or attract galleries or collectors, but because the path

of silence and withdrawal is the only one that allows access to art's

secrets," he says.

Describing himself as "a very strict Catholic" but "not

a Catholic painter," he continuously portrays himself as being on

a quest for truth.

Regarding his frequent use of pubescent girls as subjects, Balthus says,

"I've always had a naive natural complicity with young girls,"

and "I always reject stupid interpretations that my young girls are

the product of an erotic imagination."

These statements are bound to raise eyebrows, and they undoubtedly contain

some amount of denial. But as much as Balthus refuses to accept the erotic

implications of his images, the integrity of his overall agenda as an

artist is believable.

In fact, the most pleasurable passages of the book are those in which

Balthus is not defending himself or trying to set the record straight,

but instead reveling in the magical process of making art.

In the end, he remains mysterious. Nonetheless, he stands as a painter

whose ardent devotion to the life of a secluded artist continues to intrigue.

Vanished Splendors: A Memoir

By Balthus, as told to Alain Vircondelet

Ecco Press, 272 pp., $29.95.

______________________________________________

This article appeared in The Plain

Dealer, January 19, 2003

© 2007 Dan Tranberg. All rights reserved.

|

|

|