|

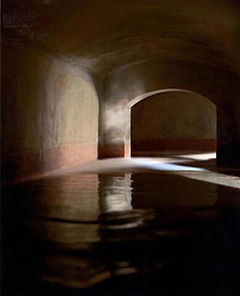

James Casebere, Nevisain Underground #2, 2001 James Casebere, Nevisain Underground #2, 2001

James Casebere, Yellow Hallway #2, 2001 James Casebere, Yellow Hallway #2, 2001

James Casebere, Monticello #3, 2001 James Casebere, Monticello #3, 2001

|

|

Picture Paradox

By Dan Tranberg

Photography has reached new heights in recent years, thanks

both to an increase in available technology and to the talents of a generation

of artists who are using it in ways not previously possible.

Among them is James Casebere, whose haunting exhibition, "Picture

Show: James Casebere," opened last week at the Museum of Contemporary

Art Cleveland, formerly the Cleveland Center for Contemporary Art.

Casebere constructs tabletop architectural models using paper, plaster

and Styrofoam and then photographs them. But rather than printing his

images in the conventional way, in a darkroom, he scans them into a computer

and prints them with a Lambda printer, an enormous, super-high-quality

laser printer.

Using this process, Casebere has made photographs as large as 8 feet by

12 feet that are sumptuously rich and detailed. And he's not alone. Photographers

including Andreas Gursky, Jeff Wall, Thomas Struth and Gregory Crewdson

all use similar technology to make images that rival billboards and movie

screens.

That's part of the idea. Unlike many art photographers, even those from

the recent past, Casebere is more interested in the context of everyday

life than he is in the insular world of fine-art galleries. He has even

placed his work anonymously on the streets of New York City in order that

it might be seen by a range of viewers.

But as much as Casebere is interacting with society, his work looks nothing

like the art of social activists of the past. Rather than favoring easily

digestible information, he creates subtle, dreamlike images that tap into

deeply subconscious anxieties.

Many of Casebere's photographs look as though they were captured the day

after a disaster, such as a flood or a nuclear explosion. There's no real

indication of what exactly happened, but each image shows a room or hallway

that is flooded with water or is stripped of its functionality. At the

same time, each scene is strangely serene, often including the calming

suggestion of sunlight streaming through a small window.

This use of paradox is at the core of Casebere's strength as an image-maker.

Nothing is just one thing. His work is both beautiful and terrifying,

both soothing and full of anxiety.

From another angle, Casebere is toying with an issue that has become a

hot topic among contemporary photographers: the relationship between fact

and fiction. While he obviously goes to great lengths to make his models

realistic and to light them in a way that simulates reality, it remains

clear when viewing his scenes that they are, indeed, models.

This is not a matter of failing to produce a believable illusion. It is

part of the program. By allowing his models to retain some sense of artificiality,

Casebere is acknowledging the essential artificiality of his medium, the

fact that all photographs are constructions in some sense.

But in spite of the fact that the places you see in his work are models,

on an emotional level Casebere's images are as real as any dream or visual

impression. They trigger all kinds of thoughts and feelings, much in the

same way that movies do.

The richness and believability of Casebere's scenes, as well as their

emotional depth, is partially attributable to the artist's interest in

history. A series of images that resemble prison cells, for example, was

preceded by extended visits to actual prisons and extensive research into

the history of the prison system.

The same is true of a series based on Thomas Jefferson's Monticello and

another based on an academy in Massachusetts. Interviews with Casebere

reveal that his thoughts about these places delve deeply into the social

implications of the systems that created them.

As with all great art, the ideas contained within Casebere's work expand

as you look at it. His photographs are not only big, gorgeous images that

take advantage of cutting-edge technology, but also artful representations

of big ideas.

______________________________________________

This article appeared in The Plain

Dealer, December 13, 2002

© 2007 Dan Tranberg. All rights reserved.

|

|

|