|

William Kentridge William Kentridge

William Kentridge William Kentridge

William Kentridge William Kentridge

|

|

South African artist appeals to conscience

By Dan Tranberg

Less than 10 years ago, William Kentridge was an obscure artist from Johannesburg,

South Africa.

Now, he’s one of the most talked-about artists alive today.

The superb exhibition, “William Kentridge Prints,” on view

at the College of Wooster Art Museum through Sunday, March 6, makes it

easy to see why.

Organized by the Faulconer Gallery at Grinnell College, it is the first

major exhibition of Kentridge’s prints, featuring 120 works produced

over the course of 28 years.

Best known for his films, which are often made using stop-action animation

and charcoal drawings, Kentridge is a remarkably diverse artist whose

work draws upon a wide range of styles and traditions.

Beautifully displayed, the show captures both the vast scope of his work

as well as the depth of his interests in humanitarian subjects.

The son of two prominent South African anti-apartheid attorneys, Kentridge

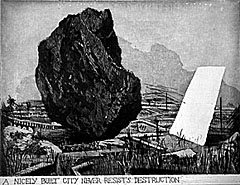

often deals with issues of societies in despair. A dramatic, 1995 engraving,

“A Nicely Built City Never Resists Destruction,” for instance,

depicts a desolate postindustrial city facing a cataclysmic problem. An

enormous boulder appears to have dropped from the sky, landing among roadways

and telephone poles.

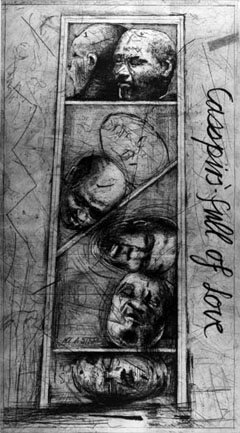

Other works address the atrocities of a tyrannical government more directly.

“Casspirs Full of Love” shows a segmented container full of

severed heads. The word “Casspirs” is a reference to a type

of military vehicle used by the South African police in the 1980s. Kentridge

often makes such references without depicting the objects literally, speaking

in a symbolic language that cuts to the heart of the situation.

In this respect, his work is often reminiscent of that of the German Expressionists,

whose imagery was similarly born out of the carnage of World War I.

Much as other art historical comparisons can be made (Francisco Goya’s

“Disasters of War” series is an obvious one) Kentridge is

most remarkable for the range of his technical and stylistic explorations.

It’s clear that he is always looking for new ways to express ideas.

Even within the limitations of print media, he is constantly pushing boundaries.

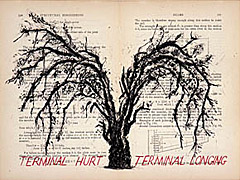

A number of works are printed over pages from an old set of encyclopedias,

for instance, rather than sheets of white paper.

In other works, roughly torn sheets of black paper are used to create

silhouetted figures, referencing the tradition of shadow puppet theatre.

Many of Kentridge’s prints relate either to his filmmaking process

or to his conception of theatrical productions. A suite of six etchings

in the exhibition comes from his 1999 film “Sleeping on Glass.”

In the show’s copiously illustrated catalog, Kentridge explains

that the film was made to be projected onto a mirror, so that the projected

image is transposed over the viewer’s reflection. Similarly, the

corresponding prints merge images from printing plates with those of preprinted

book pages, often with related subjects.

Yet another technique he uses is the creation of anamorphic images, which

appear oddly distorted unless they are viewed in a cylindrical mirror.

One such work from 2001 titled “Medusa” is displayed in the

gallery, referencing a subject that, according to mythology, was too brutal

to be viewed directly.

All of these ideas feed into larger themes of the human predicament, and

how we deal with it. Much as particular historical references can be found

in his work, Kentridge speaks to the universal more than the specific.

The realities of violence and mayhem certainly contribute to his world

view. But his response tends to place the burden of life squarely on the

shoulders of the individual, and therefore, the viewer.

Such a powerful humanitarian statement is rare in the landscape of contemporary

art, which has generally focused on more esoteric art-related issues for

years. That’s one reason Kentridge, at age 50, has quickly become

one of the most fascinating and important artists of our time.

______________________________________________

This article appeared in The Plain

Dealer , February 26, 2005

© 2007 Dan Tranberg. All rights reserved.

|

|

|