|

Michelangelo: Drawings and Other Treasures from Michelangelo: Drawings and Other Treasures from

the Casa Buonarroti, Florence, catalogue cover the Casa Buonarroti, Florence, catalogue cover

Michelangelo

Buonarroti, Nude Seen from Behind, Michelangelo

Buonarroti, Nude Seen from Behind,

1504-1505,

collection Casa Buonarroti, Florence 1504-1505,

collection Casa Buonarroti, Florence

Michelangelo

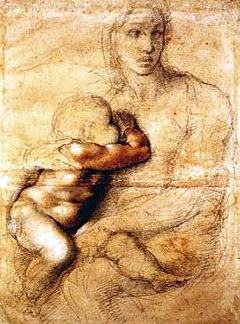

Buonarroti, Madonna and Child, Michelangelo

Buonarroti, Madonna and Child,

1525, collection Casa Buonarroti, Florence 1525, collection Casa Buonarroti, Florence

|

|

A Rare Chance

By Dan Tranberg

When it comes to artists who have been almost universally hailed as geniuses,

few in the history of Western civilization rival the great master of the

Italian Renaissance, Michelangelo Buonarroti.

The consummate Renaissance man, he and his diverse body of work remain,

even today, as benchmarks of artistic accomplishment.

Surprisingly, fewer than a dozen drawings by Michelangelo, and not a single

painting or sculpture, can be found in American collections. That's one

reason why the exhibition "Michelangelo: Drawings and Other Treasures

from the Casa Buonarroti, Florence," on view at the Toledo Museum

of Art, is nothing short of a revelation.

But what it reveals is not the fabled Michelangelo we read about in books:

It's the man behind the masterpieces.

The show features 21 of Michelangelo's drawings and one wax sculpture,

making it, by far, the greatest concentration of works by the Italian

master that can be seen in America.

Among the exhibition's highlights are "Study for the Head of Leda,"

from 1530, a remarkably subtle drawing done in red pencil. Though it's

easy to assume that the drawing depicts a woman, scholars have concluded

that the model was likely to have been Antonio Mini, one of Michelangelo's

male pupils.

The drawing's pristine condition is astonishing in itself, suggesting

that over the course of the 471 years since it was created, its artistic

importance was without dispute and it was always handled with extreme

care.

Others of Michelangelo's drawings were clearly handled more roughly, probably

by the artist himself. Many show creases, tears and scribbles across their

surfaces. But these are among the most revealing, and, in many ways, the

most enjoyable drawings to see: Though perfection was undoubtedly Michelangelo's

aim, the more casual side of his process allows us to see him as an artist

who, however gifted, still had to work to achieve greatness. Though it's

difficult to imagine, Michelangelo reportedly wished to burn many of the

preliminary sketches he had made before he died in Rome at the age of

89.

According to one of his contemporaries, he wanted "not to appear

anything but perfect." And though his attitude is certainly understandable,

it is through these works that we catch glimpses of him not only as a

genius, but also as a human being.

A sense of the artist's life and family pervades the exhibition. In fact,

more than half of the 47 works on view are not by Michelangelo, but are

part of the collection of the Casa Buonarroti, the artist's family home

in Florence.

A few of these peripheral works are depictions of the artist, the most

notable being "Bust of Michelangelo," a startling bronze that

greets viewers of the exhibition immediately upon entering its first room.

Interestingly, the sculpture was done in two stages and is attributed

to two artists. The first, Daniele da Volterra, a close friend of Michelangelo's,

is thought to have sculpted the head just after Michelangelo's death in

1564.

But when he died two years later, it is believed that the Flemish sculptor

Giambologna took over, finishing the work in 1570.

With its somber, world-weary gaze, the realistic bronze sculpture gives

you the feeling that Michelangelo is present in the room. And in a sense,

he is, as both an artist and as a patriarch of a family who actively promoted

the artist's fame after he died.

Much of the exhibition's first room is devoted to a diverse assortment

of works from the Casa Buonarroti's collection. All are intriguing objects,

but some are slightly puzzling as to their exact relationship to Michelangelo.

For example, an Etruscan urn dated from before 90 B.C. bears no obvious

relation to Michelangelo's work or to that of his offspring. The same

is true of a balsam jar from the third century B.C., which entered the

Casa Buonarroti's collection long after Michelangelo's death, probably

in the early 18th century. The presence of these objects is a testament

to the legacy of the Buonarroti family collection, but they tell us little

about the artist.

By far the most precious jewels of the exhibition are Michelangelo's own

works. As one enters the exhibition's second area, an octagonal room with

arched doorways that could hardly be more perfect as a setting for Michelangelo,

the centerpiece of the room is again startling.

It's "Madonna and Child," a drawing done in black and red pencil,

white lead and ink on paper in 1525.

Curiously, the drawing was done on a support made by gluing two sheets

of paper together. One can't help but assume that this implies that Michelangelo

intended it only as a study.

But as with nearly all of his studies, it is intensely revealing of the

artist's process, one of endless exploration into the nuance of his figures.

The child is particularly intriguing for his overly developed musculature,

recalling Michelangelo's signature use of muscular male figures as an

embodiment of beauty and perfection.

In the two remaining rooms of the exhibition, surprises pop up at nearly

every turn.

A wonderful sheet dated between 1508 and 1512 shows both a sonnet in Michelangelo's

own handwriting and a playful self-portrait of the artist painting the

ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

A pen-and-ink sketch from 1518 attributed to Michelangelo includes a list

of foods for three meals and a series of quick illustrations of each item.

Most interesting with this sheet is the fact that it is done on the back

of a letter sent to Michelangelo March 18, 1518. One might see this as

another hint of the artist's human quirks: Maybe Michelangelo was something

of a tightwad who reused paper though he could clearly afford plenty.

Organized by the High Museum of Art in Atlanta in conjunction with the

Casa Buonarroti in Florence, "Michelangelo: Drawings and Other Treasures"

is a must-see show for anyone interested in Renaissance art. Sadly, the

exhibition will not travel to any other venues. It went to Toledo after

its presentation at the High this summer, and after closing in Toledo

Nov. 25, will return to Italy.

Short of a trip abroad, the show is the closest you can come to getting

a rich sense of Michelangelo as a genius and a real person.

To the credit of the High Museum and the Toledo Museum of Art, it accomplishes

both simultaneously.

______________________________________________

This article appeared in The Plain

Dealer, October 7, 2001

© 2007 Dan Tranberg. All rights reserved.

|

|

|