|

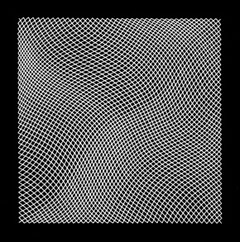

Julian Stanczak, Tense Cluster, 1966 Julian Stanczak, Tense Cluster, 1966

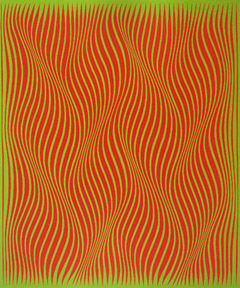

Julian Stanczak, Obsession II,

1965, collection of Julian Stanczak, Obsession II,

1965, collection of

Neil Rector, Columbus, Ohio Neil Rector, Columbus, Ohio

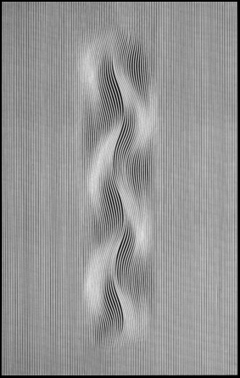

Julian Stanczak, Elusive, 1995, collection of Julian Stanczak, Elusive, 1995, collection of

Robert Mann Robert Mann

|

|

Eye to Eye

By Dan Tranberg

It’s been a while since art explicitly about visual perception has

been at the forefront of the art world. Though an acclaimed retrospective

of works by British Op artist Bridget Riley opened at New York’s

Dia Center for the Arts earlier this year, the visually dazzling geometric

patterns of Op art made only a brief splash in the mid-’60s, then

were quickly disseminated as sources for fabric designs and psychedelic

bric-a-brac.

A recent resurgence of optically oriented abstraction has stirred new

interest in Op art. Lucky for us, its key pioneer, Julian Stanczak, lives

right here in Cleveland. A major retrospective of Stanczak’s work,

currently on view at the Cleveland Institute of Art’s Reinberger

Gallery, traces the progression of Stanczak’s art from his early

studies through works that typify Op. But what the show celebrates is

not the "Cleveland connection" to a famous art movement; it

is the remarkable life and work of an artist determined to find clarity

in a world of chaos.

Julian Stanczak has been making art for nearly six decades. In less than

half that time, he became a prominent American artist, represented in

New York by the Martha Jackson Gallery and featured in the 1965 exhibition

The Responsive Eye at the Museum of Modern Art. Remarkably, he accomplished

all of this after losing the use of his right arm as a precocious (right-handed)

teenager.

By the time Stanczak arrived in Cleveland at the age of 21, he had experienced

far more horror than most witness in a lifetime. In 1940, when he was

11 years old, Stanczak and his family were forced from their home in Poland

into a Siberian labor camp. They escaped in 1942, traveling on foot until

they met up with the exiled Polish army. Out of desperation, Julian (at

age 13) had to leave his family, lie about his age, and join the army

"because they had food." But severe illness and the loss of

the use of his right arm left him no choice but to desert.

He found his mother and sister in a refugee camp and retrieved his brother

from an orphanage. Together, the family traveled to India, then finally

to a community of Polish exiles in the jungles of British Uganda, where

they were detained for the next seven years, living in straw huts. Because

Stanczak’s father was serving in the Polish Army under British command,

and Poland’s newly formed Communist government prevented the family

from returning to their homeland after the war, the Stanczaks were eventually

granted permanent residence in England. After two years, they emigrated

to the U.S., first to New York, then to Cleveland, where jobs were available.

Soon after arriving, Stanczak enrolled as a student at the Cleveland Institute

of Art.

"I was born at age 21 in Cleveland, Ohio," he recently remarked

while standing in front of one of his new paintings. But though Stanczak

has every right and reason to feel that way, his life and his art stand

as a testament to the triumph of his will. The Op art of the 1960s is

only part of the picture. The most exciting part of the show, in fact,

is Stanczak’s recent work, in which seemingly random elements are

incorporated into linear systems, producing images of amazing visual subtlety

and perceptual complexity.

Considering his tumultuous youth, it’s not difficult to surmise

that Stanczak sought order and control in art. Tracing his early works,

one can see a clear progression from an intuitive attraction to rhythmic

patterns to an increasingly systematic analysis of form and color. Crucial

to these early developments is Stanczak’s tutelage under the man

he referred to as an "expert in the mystery of color," Josef

Albers. Stanczak studied with Albers at Yale, where he received his MFA

in 1954. Clearly, Albers helped Stanczak refine his understanding of the

interaction of color. But it was Stanczak’s own ingenuity that lead

him to develop images accentuating physical sensations associated with

vision.

When Martha Jackson chose the title Optical Paintings for Stanczak’s

first solo show at her gallery in 1964, and a Time magazine review contracted

optical to "Op," the term "Op art" was born. But neither

Stanczak nor Albers approved of it. Albers commented at the time that

"perceptual art" would be a more appropriate term, undoubtedly

because the word "optical" connotes only sight and not the more

complex issues of perception, into which Stanczak was clearly tapping.

Regardless of art-world buzzwords, Julian Stanczak’s lifetime of

work is an odyssey that will likely take years to fully appreciate. Perhaps

the greatest benefit of seeing a half-century worth of his work is the

inevitable realization that Stanczak’s art has very little to do

with a passing trend. Rather, it’s about the basic human need to

understand our connection to the physical world. Ultimately, his paintings

are not lessons in vision; they’re lessons in life.

______________________________________________

This article appeared in The Free

Times , September 12, 2001

© 2007 Dan Tranberg. All rights reserved.

|

|

|