| |

SELECTED REVIEWS

AND ARTICLES

Balthus

Hernan Bas

Max Beckmann

Eric Bogosian

Michaël Borremans

Louise Bourgeois

James Casebere

Manierre Dawson

Christine Hill

Jim Hodges

Dennis Hollingsworth

William Kentridge

Michelangelo

Pablo Picasso

Dana Schutz

Julian Stanczak

John Szarkowski

Ai Yamaguchi

|

|

FEATURED ARTICLE

Spiegelman extols cartoons as art

By

Dan Tranberg By

Dan Tranberg

Most people don't usually think of cartoons

as art. Despite the many skills required to create engaging stories though

images, cartoons and comic books remain entrenched in a category of artlike

activities in the shadow of traditionally esteemed art forms such as painting

and sculpture.

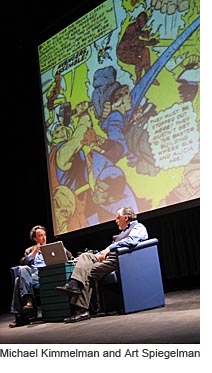

The state of comics as art served as the backbone for a public dialogue

recently at Cleveland Public Theatre on Cleveland's West Side. Pulitzer

Prize-winning artist and comic-book creator Art Spiegelman shared the

stage with Michael Kimmelman, chief art critic for The New York Times.

The event was the latest in an ongoing series of public talks called "Spectrum:

The Lockwood Thomson Dialogues," presented by the Cleveland Public

Library in partnership with the nonprofit Cleveland Public Art.

With Spiegelman's work projected on a large screen above the stage, Kimmelman

began the conversation by recalling the notorious 1990 exhibit at the

Museum of Modern Art in New York called "High and Low: Modern Art

and Popular Culture." That show effectively opened the door for a

wide range of topics, including the limited ways in which the art establishment

has embraced cartoons.

Spiegelman said he found the "High and Low" exhibition to be

"distasteful," particularly because it included very few comics.

He explained a hierarchy in the art world in which "painters are

on top" and "cartoonists are on the bottom."

Through the hour-long conversation, Spiegelman gave numerous examples

of how comics function as art, defining the genre at one point as "picture

writing" and saying that "stained-glass windows were the first

comics" because they are early examples of artists telling stories

in pictures.

Alongside this discussion, Spiegelman talked about his professional career,

which began when he was 16; he is now 59.

In addition to being known as a champion of comics as art, Spiegelman

is famous for his comic memoir "Maus I: A Survivor's Tale,"

released in 1986, and "Maus II: And Here My Troubles Began"

(1991).

"Maus," which tells the story of Spiegelman's parents surviving

the Holocaust, received great critical acclaim and led to a major exhibition

at the Museum of Modern Art in 1992 as well as a Pulitzer Prize that same

year.

His other accomplishments include successful commercial endeavors. He

invented Wacky Packs, stickers that parodied consumer products, in the

late 1960s. Later, he came up with Garbage Candy, miniature plastic garbage

pails filled with garbage-shaped candy.

Spiegelman also spent a decade working as an illustrator for the New Yorker.

Among the last and most unforgettable covers he did for the magazine,

just after the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, was a depiction of the World

Trade Center's twin towers as a black silhouette against a slightly lighter

black backdrop.

Considering the vast breadth of Spiegelman's experience and accomplishments,

it's no surprise that he did the bulk of the talking during the dialogue.

Sensibly, Kimmelman functioned mainly as a guide.

In the lobby, after the talk, Kimmelman remarked, "Interviewing Art

is like turning on a switch."

___________________________________________

This article appeared in The Plain

Dealer, May 25, 2007

© 2007 Dan Tranberg. All rights reserved.

|

|

|